Topics in Photographic Preservation 2011, Volume 14, Article 8 (pp. 44-49)

Presented at the PMG session of the 2010 AIC Annual Meeting in Milwaukee, Wisconsin

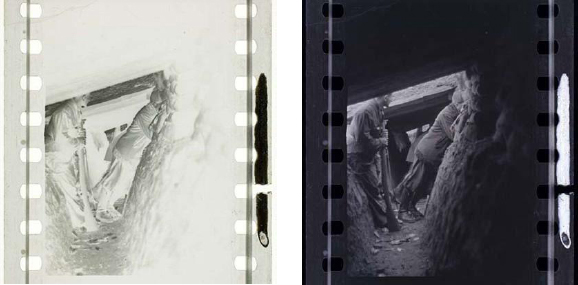

The discovery of “The Mexican Suitcase,” an important group of 35mm photographic negatives of the Spanish Civil War taken by pioneers of photojournalism --Robert Capa, David 'Chim' Seymour, and Gerda Taro--presents a very complex preservation and access challenge.

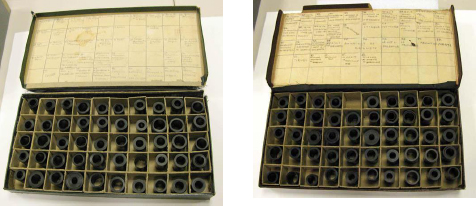

The metaphorical suitcase is an intricate object consisting of three mat board boxes, two of which contain about one hundred 35mm nitrate film rolls that previously had been thought to be lost.

These two boxes of negatives were the subjects of this project.

Two containers from that time period with the negative film rolls

This case study describes the development and execution of a conservation plan for the film rolls and their historic housing. The challenges encompassed accessing the historic image content and developing a long-term preservation proposal for this unique group of associated photographic objects.

More than just a group of 35mm negatives, the contents of the boxes are an important legacy of a still vital period of Spanish history. Their preservation is an essential link to the history of both Spain and Photography.

The story starts in 1940 when the Photographer Robert Capa, afraid of losing the negatives due to World War II, gave them to his darkroom assistant in Paris, Csiki Weisz. Csiki put them in a safe place and took them to Marseille, France a year later. From there, somehow, the negatives ended up in hands of the Mexican diplomat Francisco Aguilar González who settled in Vichy. At some point, the negatives made their trip to Mexico. All during this time the negatives were thought to be lost.

The Photographers of the Mexican Suitcase, Robert Capa, Gerda Taro and David “Chim” Seymour, met between 1934 and 1935 in Paris, an important cultural center at the time. They were asked by the magazines VU and Paris Match to document the Spanish Civil War. This was a conflict that occurred in Spain from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican and the Nationalist groups. This event was considered the laboratory for World War II. The War ended with the victory of the Nationalist group headed by General Francisco Franco on April 1939.

The “Mexican Suitcase” was brought to light at the end of 2007 when the material appeared in Mexico City in the hands of the filmmaker Benjamin Tarver. Tarver and the International Center of Photography made the proper arrangements for the transfer of the object to New York City on December of that same year.

The news about the discovery of the so-called “Mexican Suitcase” was of great interest to the international press. Since January 2008 there had been invaluable and lasting attention to this event and its evolution.

Kennedy, Randy, “The Capa Cache.” The New York Times (January 27, 2008) AR1 Private collection.

The Curators of the ICP asked the assistance of the Kay R. Whitmore Conservation Center of the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY regarding a safe way to access the photographic material and its proper conservation. Grant B. Romer and the specialist in digitization of photographic materials, Michael Hager, carried out a visual diagnosis in-situ of the film rolls. They found fragile and tightly curled 35mm nitrate base film. Also, the filmstrips presented several lengths going from the 2 frames strip to 42 frames strip. The primary consideration was preventing damage during handling of the tightly curled rolls; a secondary concern was the already-broken sprocket holes and the cut filmstrips that mark certain frames. The challenges, in order of priority, were to safely access without causing damage and/or compromising image information and to propose a suitable storage method.

The negatives from the Mexican Suitcase never left the care of the International Center of Photography. Given the circumstances, the problem had to be solved without regular access to the original materials. For that reason, the condition of the object was re-created in the conservation laboratory in Rochester, NY using non-valuable 35mm nitrate film.

The project was divided into two stages: the first stage consisted on solving the access to the film without causing damage. The second stage consisted of the recommendations and long-term proposal for the object. The plan was based on the criteria that the format and the information had to be kept in its original condition.

This means:

• Maintaining the original format

• Minimize manipulation to avoid damage

• The access for reproduction purposes has to be done without cutting the film rolls into 4 to 6 frame strips

• Avoid moisture application to flatten the support

• Balance between conservation and curatorial purposes

First Stage: Access

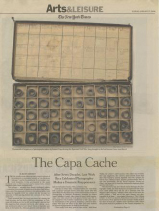

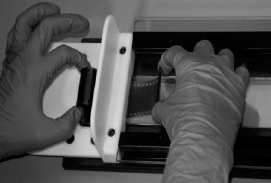

The solution for the access was to design a device that allows the film to be held flat only in certain areas, thus avoiding stress to the whole strip of film. This device has to be gentle with the material (emulsion and base support) while allowing the recording of all the information contained on the film such as brand name, notations, sprocket holes and original discoloration of the film base.

We looked into options for the scanning of 35mm negative film rolls in the market and in the motion picture technology. The options in the market did not satisfy our needs. The commercial scanner specifically designed for 35mm film doesn’t solve the problem of working with long length film rolls. Further it doesn’t allow the recording of all the information contained in the film. The scanner used for motion picture film was also not suitable because it is based on a gears mechanism which could cause further damage since the film rolls presented some broken sprocket holes.

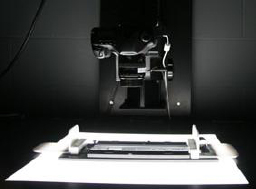

After approximately five months of trial and error the team constituted by Grant B. Romer, Inés Toharia, and myself created the Planar Film Duplicating Device (PFD2) with the contribution of Arnold Vanderburgh. This was made of all inert and safe materials such as Teflon, glass and brass. All of them are extremely gentle with the nitrate film while allowing the recording of all the contained information.

The PFD2 was designed to be used in a copy stand. This device allows working with 35mm film with different lengths. The negative photographic images can be captured either with an analogue or digital camera.

The use of the device and the capture of the photographs were done in the ICP. It was recommended to capture one frame at a time using a 100mm lens. To guide the operator during the capture process an accurate Instruction Manual of the PFD2 was written by Inés Toharia and myself.

The PFD2 allows the capture of all the information contained and the condition of the film.

David ‘Chim’ Seymour. Image Courtesy of the International Center of Photography

Half of the flaps were made of heavy brass mat with a coating (E-Kote®) and the other half was made of glass. This way the film was kept flat from the edges while the transparency of the glass allowed the capture of the whole film.

Insertion of the film roll

Weights to help keep film in place

PFD2 designed to be used in a copy-stand

Second Stage: Long-term Preservation Proposal

The artifactual value of the Suitcase's original storage format suggested an unusual preservation proposal: I recommended that ICP store the nitrate film rolls in cold storage in their existing curled state in replacement mat board boxes that retain the original order and handwritten information. Meanwhile, the original containers should be stabilized through conservation treatment.

The film rolls would be kept in its original shape and be placed in an archival box with the same dimensions that the original boxes. The mat board used to re-create the distribution inside the boxes would serve as a moisture trap.

For storage and exhibition purposes the object had to be documented in depth: dimensions, description of the object and condition. Once documented and film rolls in cold storage, the boxes need to be treated.

A set of facsimiles would be exhibited in the original boxes. Acetate 35mm film was suggested because of similarities in color and shape with nitrate; even though polyester is more stable, it is too rigid and its coloration is not as close to nitrate as acetate is.

The proposed solution to access the images was favorably implemented and its success brought international attention to the field of photograph conservation and inquiries from institutions with similar cases.

The long-term storage proposal and recommendations for exhibition were given to Cynthia Young, Curator and head of the Mexican Suitcase project at the International Center of Photography, and will be the basis for the museum's decision concerning how to best preserve and display the Mexican Suitcase.

The problem of the Mexican Suitcase was significant and a common one. The solution we devised was very successful. None of its negatives suffered damage and all the 35mm film rolls were digitized without compromising the quality of the images. It took about eight months to arrive at a workable solution and another three months to get all the capture work done.

This project would not be possible without the generosity of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the support of Mrs. Angelica Rudenstine. I would like to thank above all Grant B. Romer for his guidance on this project and Inés Toharia Terán for her expertise regarding film materials and her invaluable contribution and support. Also thanks to Arnold Vandenburgh for his contribution to the design of the Planar Film Duplicating Device. Thanks to the Staff of the George Eastman House, particularly to Stacey Vandenburgh and the Fellows of the 5th Cycle.

My gratitude to the Image Permanence Institute specially James Reilly, Doug Nishimura and Jean-Louis Bigourdan for their advice and expertise concerning nitrate film and cold storage techniques.

Thanks to the International Center of Photography in particular to Cynthia Young and Christopher George.

My appreciation goes to the American Institute for Conservation and the Photographic Materials Group for the dissemination of this paper.

Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. New York: Penguin Books, 2001.

Bigelow Sue. Cold Storage of Photographs at the City of Vancouver Archives. N.p.: Canadian Council of Archives, March 2004.

Bondi, Inge. Chim: The Photographs of David Seymour. Edited by Catherine Chermayeff, Kathy McCarver Mnuchin, and Nan Richardson. New York: Umbra Editions, 1996.

Feinberg, Milton. Techniques of Photojournalism. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1970.

Gidal, Tim N. Modern Photojournalism: Origin and Evolution, 1910-1933. New York: Macmillan, 1973.

Langdon-Davies, John. Behind the Spanish Barricades. 3rd ed. New York: Robert M. McBride & Company, 1937.

Nissen, Dan, ed. Preserve the Show. Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002.

Reilly, James M., and the Image Permanence Institute. Storage Guide for Color Photographic Materials: Caring for Color Slides, Prints, Negatives, and Movie Films. New York: State University of New York Press, 1998.

Smither, Roger, ed. This Film is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film. Brussels: Fédération Internationale des Archives du Film, 2002.

Schaber, Irme, Richard Whelan, and Kristen Lubben. Gerda Taro. New York: International Center of Photography, 2007.

Wagner, Sarah S. “Cold Storage Options: Costs and Implementation Issues,” Topics in Photographic Preservation, Vol.12. Photographic Materials Group. Washington D.C.: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 2007.

Warda, Jefrrey. The AIC guide to Digital Photography and Conservation Documentation. Washington D.C.: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 2005.

Whelan, Richard, This is War! Robert Capa at Work. New York: International Center of Photography, 2007.

Whilhem, Henry, and Carol Brower. The Permanence and Care of Color Photographs: Traditional and Digital Color Prints, Color Negatives, Slides, and Motion Pictures. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress, 1993.

The Film Preservation Guide: The Basics for Archives, Libraries and Museums. San Francisco: National Film Preservation Foundation, 2004. www.filmpreservation.org

McCormick-Goodheart, Mark H., “On the Cold Storage of Photographic Materials in a Conventional Freezer Using the Critical Moisture Indicator (CMI)Packaging Method” July 2003. http://www.wilhelm-research.com/subzero/CMI_Paper_2003_07_31.pdf

Paper presented in Topics in Photograph Preservation, Volume Fourteen have not undergone a formal process of peer review.