Topics in Photographic Preservation 2003, Volume 10, Article 9 (pp. 86-97)

Presented at the 2003 PMG Winter Meeting in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Matt albumen papers were very popular in Germany and Austria at the beginning of the 20th century. Matt surfaces that left details obscure met the intentions of the photographers to focus on the essential part, on the distribution of light and shadow. We can find many examples of this variation of albumen papers especially in portrait photography. The Viennese studio d'Ora was famous for its portraits, many of which have formed our visual concept of artists like Gustav Klimt or Alban Berg (figure 1). Original prints, among them matt albumen papers, and negatives from this studio housed at the Austrian National Library allowed direct comparison between negative and print. In a common project we were able to study the collection of 2500 original negatives and of 80 vintage prints. From the perspective of a photographer and a conservator, we focused on the materials used by the studio and their interaction with the artistic intent.

Figure 1: Alban Berg, Vienna 1909, modern print on RC-paper, 24×18 cm, OeNB, POR, Neg. 203.481:D

In 1895 Arthur von Huebl described the production of matt albumen papers in the journal “Photographische Rundschau” (Huebl 1895): Egg white is beaten to froth and left for a couple of hours until it becomes liquid again. The liquid, albumen, is mixed one to four parts with a two percent solution of arrowroot starch. Sodium chlorid (2%) is added to both the albumen and the starch solution. The mixture is brushed on to the paper evenly and thinly. A dry brush is applied in circular movements until all gloss is gone. The paper is left to air dry. The dry paper is sensitized by floating on a silver nitrate solution (500ml water, 60g silver nitrate, 8g citric acid). Huebl (Huebl 1896) advises to contact print matt albumen papers slightly humid to achieve better contrast. The papers print a deep reddish brown. This colour can be modified by toning in gold and/or platinum toners. Gold toning results in warm brown tones, platinum toning in black with a brown tint. Huebl appreciated the distinctive warm brown tones of platinum toned albumen prints that can not be achieved with pure platinum prints. Untoned matt albumen papers look very similar to salted paper prints, in colour and texture. Under magnification the thin albumen layer hardly obscures the paper fibres. The surface is only slightly more glossy than on a normal salted paper print. Platinum toned matt albumen papers can be confused with platinum prints but in comparison with the latter their tone is warmer and contrast is stronger.

The Viennese company E. Just started to produce matt albumen papers commercially according to Huebl (Wentzel 1928). But most famous were the papers made by the German company Trapp & Muench. In Friedberg in Hessen Trapp & Muench started to produce matt albumen papers in 1902. In many photographic journals these papers were praised because of their quality and the noble and artistic effect that could be achieved by them (Krimse 1905, Neuheitenbericht 1907, Apollo 1907). Theodor Krimse appreciated these papers because they were easy to work with, stayed flat (in contrast to glossy albumen papers), were easy to tone and to retouch. Dührkopp (Dührkopp 1904) praised the rich tonal scale that could be achieved. The matt surface obscured small details which would normally distract from the overall impression. In a Trapp & Muench catalogue dating from 1913, 13 different paper qualities of matt albumen papers can be found, ranging from thin paper to cardboard (Trapp & Muench 1913). All these paper qualities were available in smooth and rough as well as white and off white. Some of these papers had a corn structure. Together with the Berlin photographer Nicolas Perscheid Trapp & Muench developed a matt albumen paper on Japanese paper. Perscheid and Dr. Trapp worked closely together. Trapp & Muench used to sent first examples of new papers to Perscheid where the copyist Hoeppner tested them (Benda). Matt albumen papers were also produced by Schwerter in Dresden under the name Albumat and by Brune & Hoefinghoff in Barmen under the name Albumon-paper but their use was not as wide spread (Wentzel 1928).

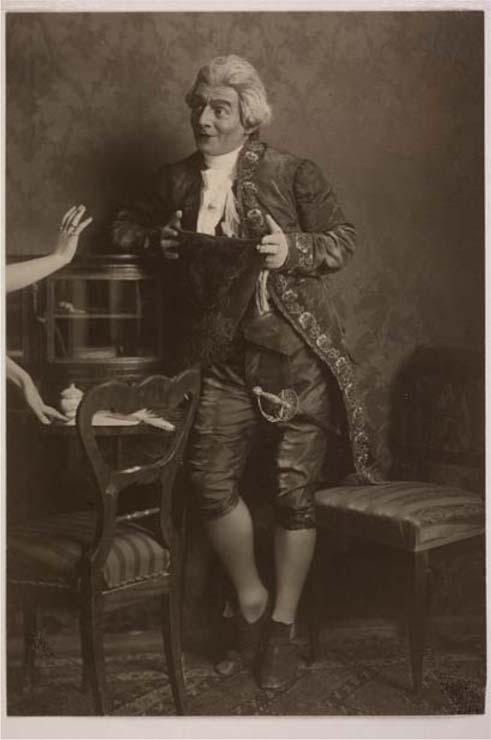

Dora Kallmus, the head of the studio d'Ora-Benda, was born in 1881 in Vienna, into a wealthy Jewish family. Her wish to become a photographer met severe obstacles. At that time it was impossible for a woman to study photography in an apprenticeship or at the school for graphic arts and photography in Vienna. With the help of her uncle, Dora Kallmus was able to do a six months internship with the famous Berlin photographer Nicola Perscheid. In her memories (Kallmus) she describes work with the impulsive tutor: “By his demands I gained a capital of knowledge and for the same reason lost a capital of nerves.” Together with Perscheid's assistant Arthur Benda, Dora Kallmus opened her own studio in Vienna in 1907. Arthur Benda was born in 1885 in Berlin. He passed an apprenticeship with Nicola Perscheid while the latter was still working in Leipzig. From 1906 to 1907 Benda continued to work for Perscheid as an assistant. Among other things he was responsible for the production of coloured prints where he experimented with many different techniques. Arthur Benda helped Dora Kallmus to plan and set up her studio in Vienna. She employed him as operator and technical head of the studio situated in the very centre of Vienna. Due to her social connections Dora Kallmus or Madame d'Ora as she started to call herself was able to well establish the studio and to reach a wide range of clients. Many artists came to the studio to have their portrait taken: painters, writers, musicians, dancers and actors, like Arthur Schnitzler, Richard Strauss or Marlene Dietrich. Even the Emperor and his family after first refusing, found their way into the studio. Actors like Harry Walden and opera singers like Marie Gutheil-Schoder especially appreciated Madame d'Ora's portraits which depict them in numerous roles (figure 2). In a very early stage Madame d'Ora started to take fashion photographs like the avant-garde designs from the Viennese workshops (Wiener Werkstaette) which were published in fashion journals. Arthur Benda intensively experimented with the coloured prints and created excellent gum and bromoil prints in different colours. In 1927 Dora Kallmus and Arthur Benda finished their cooperation for reasons that are not clearly known. Dora Kallmus moved to Paris and started a studio there. Arthur Benda stayed in Vienna and continued the studio under the name d'Ora-Benda. Despite difficult circumstances Dora Kallmus was able to establish herself in Paris and to run a successful portrait studio. Again there were many artists among her clients like Coco Chanel, Maurice Mistinguette or Colette. Dora Kallmus did a lot of fashion photography while working for the journal “Dame”. Paris suited her very well. But the invasion of the German troops forced her to abandon her studio and to flee to Southern France. After the war Dora Kallmus returned to Paris and continued her work. One of her latest and most disturbing works was a series of photographs from the Parisian slaughterhouses depicting animal carcasses. In 1961 after an accident she returned to Austria, to the house of her family in Styria, where she died in 1963. Arthur Benda had stayed in Vienna. His wife Hanny started to work with him in the studio which was a well known portrait studio. After the second world war the studio's name was changed to Benda. Arthur Benda died in 1969 and although he had never met Dora Kallmus again, he knew about her life through a mutual friend (Kemp 1980, Faber 1983).

Figure 2: Harry Walden as Riccault, Vienna 1914, matt albumen paper platinum toned, 21.6 × 14.8 cm, OeNB, POR, Pk 4269, 2.

Both Dora Kallmus and Arthur Benda were strongly influenced by Nicola Perscheid's photography who saw himself as a renewer of portrait photography. Perscheid's aim was to compose an independent image, to recreate the atmosphere of the pose. Following this tradition Dora Kallmus understood the character of portrait photography not as a mere rendering of reality but as interpretation and artistic expression. Light, the choice of sharpness and perspective were means of creating a well balanced image. Integrating the principles of pictorial photography into the workflow of a commercial studio Madame d'Ora avoided the pitfalls of pure pictorialism. Her images retained “straightness”, a tendency that became more prominent in her later work.

Most portrait studios at the beginning of the 20th century used direct but diffused light. The sitter was in focus, the surrounding remained obscure, the background indefinite. The studio d'Ora used lenses with low depth of field. Only the important parts of the image where rendered sharp. The photographer seemed to have asked himself: What deserves sharpness? What is essential? What is unessential? In the portrait of the dancer Anna Pawlowa the focus is on the face of the dancer (figure 3), in the photograph of a hat model by Krieser, the hat is sharp but the face of the lady obscure (figure 4). Dora Kallmus tried to find new and individual solutions for portraits expressing the personality of the sitter and creating a certain mood. Working with light, sharpness and perspective she freely distributed areas of importance. The results are very intimate and sensible portraits that reveal much about the personality without rudely exposing every detail.

The studio worked with punctual light sources arranging them in circular formation. A big problem of this use of light were dark shades. The solution was found in bright surfaces, which reflected light and so reduced strong contrast. Artificial light sources should imitate natural day light. The light sources were often fixed above the sitter, so that shades were almost completely outside the scene photographed. The rest of bothering shades was corrected by retouching on the negative. An example for using a very interesting formation of light is the picture of Marie Gutheil-Schoder as Salome (figure 5). The focus of the art work is the centre of the photograph - a symmetrical composition. The person is standing in the middle of the space with arms wide open. She looks to the right and not into the camera. Marie Gutheil-Schoder is flooded with light and the space around her sinks in darkness. So Salome gets a very individual character, which fits to the story of Salome, mysterious and dangerous at the same time.

Figure 3: Anna Pawlowa, Vienna 1913, modern print on matt albumen paper, platinum toned, 24 × 18 cm, OeNB, POR, Neg. 203.634:D

Figure 4: Hat model by Rudolf Krieser, Vienna 1910, modern print on RC-paper, 24 × 18 cm, OeNB, POR, Neg. 203.496:D

Figure 5: Marie Gutheil-Schoder as Salome, Vienna 1918, matt silver gelatine paper, 22.2 × 15.2 cm, OeNB, POR, Pk 4271,3

Negative retouching played an important role in the workflow of the studio which we could observe while studying the original negatives. Almost all negatives, the majority measuring 18 × 24 cm are retouched. Irregularities of the skin are retouched by pencil and by scraping. Actors and singers were photographed in the studio and later the background decoration, sometimes a whole scenery was painted on the negative using red and yellow colours as well as pencil and scraping. The portrait of Marie Gutheil-Schoder as Elektra is an example of the great routine with which these paintings were carried out. The stones on which Elektra seems to stand so firmly are all painted. Gutheil-Schoder actually stood on a little stage covered with cloth. The barely lit background provided a good even surface for retouching.

With the help of retouching, the use of light was reinforced and technical problems were overcome: Strong shades were lightened up by pencil strokes. Highlights were set or intensified with pencil. Scraping reinforced shades and dark lines. Negative retouching was a continuation of the idea to attach importance to certain parts and leave other unessential parts in obscurity. A matt varnish was often applied to the glass side. It was easier to retouch on the varnish. The varnished parts printed softer therefore details were more diffuse. But by scrapping some details could be taken out of obscurity and be rendered more sharp.

The effect of the negative retouching depends on the choice of printing paper. On matt papers retouching is less visible than on glossy papers. The studio d'Ora-Benda used mostly matt papers: matt albumen and matt silver gelatine papers. Among the vintage prints at the Austrian National Library we found many matt albumen prints, untoned and platinum toned although we could not identify any trade marks or specific companies. Both Arthur Benda and Dora Kallmus were familiar with Trapp & Muench matt albumen papers that they first encountered in the studio of Nicola Perscheid who closely cooperated with this company. In a booklet published by Trapp & Muench it is stated that at the International Exhibition of Photography in Dresden 1909 eleven portraits by the studio d'Ora-Benda printed on Trapp & Muench matt albumen paper were exhibited (Trapp & Muench 1909). We could distinguish between papers with different thickness and texture when looking at the vintage prints. There are papers with a fine corn texture and others with a rougher one. The untoned prints are generally in relative good condition showing fading only at the edges. But some are also heavily oxidized, yellowed and faded. The platinum toned prints are in far better condition. Some are slightly yellowed but otherwise exhibit no loss in the highlights. At the Institute of Science and Technology in Art, at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Katharina Dietrich performed x-ray-fluorescence- analysis on three prints. Platinum was detected but no gold. This leads us to the assumption that most prints were either left untoned or were platinum toned. Matt albumen papers render details diffuse, negative retouching like pencil strokes or scraping is not distinctly visible. The deliberate choice of printing paper is a continuation of the photographer's intent to focus on the essential.

All the original glass plate negatives, measuring 18 × 24 cm (7 × 9 1/2 in), were rehoused in lignin free paper envelopes and have now also been digitised. The parts of broken plates were secured within a matboard frame and sandwiched between two new glass plates. J-Lar tape (EIS) was used to tape the plates together. The vintage prints were treated where necessary: tears were mended with wheat starch paste and Japanese paper, losses were filled with adequate paper and toned with watercolours (Schmincke). Many prints had to be flattened by humidification and drying under weights. All vintage prints were mounted in passepartouts made out of acid free board (Canson, 1.8 mm). Some prints, for example oval formats, were mounted with inlays made out of 300g acid free board (Hahnemuehle).

For public access, modern prints were produced from the negatives on glossy RC-paper. It became very obvious that negative retouching is clearly visible on many of the glossy modern prints. Pencil strokes in the background are reproduced sharply. Scraping of the matt varnish like on the feather of Marie Gutheil-Schoder (figures 6–8) or in the face of Anna Pawlowa shows as a hatched pattern on the modern print. Modern prints on the glossy papers exhibit more contrast. In an effort to study the recipe of Huebl (Huebl 1895) modern prints from some negatives were made on matt albumen papers. The matt albumen paper was prepared according to Huebl although arrowroot was replaced by wheat starch. The starch and albumen solutions were mixed one to one. Platinum toning was done in a solution of potassium tetrachloroplatinate. On the matt albumen papers the negative retouching was not visible. With some examples we could make direct comparison between negative, vintage print, modern prints on glossy RC-paper and modern prints on matt albumen paper, like with the portrait of Marie Gutheil-Schoder. On the matt albumen modern print no strokes from retouching are visible, the overall impression is softer and more picturesque. Retouching is integrated into the final image. Comparing the different printing papers confirmed our assumption that the photographer deliberately chose the paper to achieve a certain effect.

Figure 6: Marie Gutheil-Schoder, glass plate negative, detail, feather scraped out of matt varnish on glass side, OeNB, POR, Neg. 203.655:D

Figure 7: Marie Gutheil-Schoder, matt albumen paper, detail, retouching of feather on negative not visible, OeNB, POR, Pk 4269, 5

Figure 8: Marie Gutheil-Schoder, modern print on RC-paper, detail, retouching on feather visible.

Matt albumen papers were an important medium in portrait photography in the early 20th century and available in a wide range of strengths and textures. If platinum toned, they exhibit excellent image stability. The inventory of the studio d'Ora offered the unique possibility to compare negatives, vintage prints and modern prints of the same image. Looking at the different steps of the creative process confirmed our assumption that arrangement, shot, negative, negative retouching and printing paper form a unity and have to be regarded together. The choice of material and the artistic intention are closely interwoven.

We would like to thank Uwe Schoegl, Monika Faber, the Photomuseum in Bad Ischl and the Museum of Applied Art in Hamburg for their cooperation and support. The Institute of Science and Technology in Art at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna generously offered us the possibility of X-ray-analysis.

Apollo. 1907. Vol. XIII: 127.

Benda, Arthur. undated. Von meiner Lehrzeit bei Nicola Perscheid. Unpublished typescript. Photomuseum Bad Ischl, Austria.

Dührkopp, R.. 1904. Neuzeitliche Bildstoffe und Bildausstattungen. Das Atelier des Photographen. Nr. 4.

Faber, Monika. 1983. Madame d'Ora, Portraits aus Kunst und Gesellschaft 1907–1957. Wien - Muenchen: Edition Christian Brandstaetter.

Huebl, Arthur von. 1895. Albumin-Mattpapiere. Photographische Rundschau Nr. 2: 38–42.

Huebl, Arthur von. 1896. Der Silberdruck auf Salzpapier. Halle a.S.: Verlag Wilhelm Knapp.

Kallmus. Dora. undated. Nicola Perscheid. Unpublished manuscript. Museum fuer Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg.

Kempe, Fritz. 1980. Nicola Perscheid, Arthur Benda, Madame d'Ora. Hamburg.

Krimse, Theodor. 1905. Ein Mattpapier von künstlerischer Wirkung. Der Photograph, Nr. 44: 173–174.

Neuheitenbericht. 1907. Die photographische Industrie, Nr. 8: 210–211.

Trapp & Muench Handbuch. 1913. Friedberg.

Trapp & Muenchs Matt-Albumin-Papiere auf der Internationalen Photographischen Ausstellung Dresden 1909.

Wentzel, Fritz. 1928. Die photographischen Kopierverfahren mit Silbersalzen. In Ausfuehrliches Handbuch der Photographie, vol. 4, part 1. Halle a.S.: Verlag Wilhelm Knapp.

Papers presented in Topics in Photographic Preservation, Volume Ten have not undergone a formal process of peer review.