Topics in Photographic Preservation 2011, Volume 14, Article 17 (pp. 103-120)

Presented at the 2011 PMG Winter Meeting in Ottawa, Canada.

Between 2000 and 2010, the Nederlands Fotomuseum Rotterdam, NL (NFM), has undertaken a conservation project concerning the heritage of the Georgian photographer Dmitri Ermakov. Since 1930, Ermakov’s nearly-complete archive is kept in the Simon Janashia State Museum, Tbilisi, from 2004 on, part of the Georgian National Museum group (GNM). Ermakov’s Estate comprises cameras, glass plate negatives, as well wet collodion as gelatin dry-plate, stereo photo cards, original mainly albumen prints, photographers sales albums, administrative albums and printed sales catalogues. At the end of the summer of 2010, the project was considered being completed successful. More than 19000 images, with their description, of the 19th century Caucasus area were digitized and made available.

Often final reports can be reduced to summaries of figures and numbers of completed work. After situating the photographer and his estate, I will focus on the knowledge exchange, the several obstacles and the ‘unexpected’ we had to deal with, and complete the article with a summary of the project realizations.

Dmitri Ermakov (1845-1916) started his photographer career as a student of the Military Academy in Ananuri (Georgia). In the mid 1870’s, he opened a photo studio in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. Ermakov was a very active man with great interest in geography, ethnography, archaeology and architecture. He travelled huge distances with his small caravan, depicting mainly the Caucasian Region. But he visited also Turkey and Persia and the Shah’s family. Back in Tbilisi he advertised in periodicals and newspapers to inform his clientele about the new images they could purchase. Part of Ermakov’s business was the selling of single mounted photographs and custom-made photo albums and portfolio albums. Visitors of his studio could choose images out from the photo sale albums, in which photographic prints were arranged according to subject, region or country and type.

Dmitri Ermakov was a member of the Caucasian Section of the `Moscow Archaeological Society`, The `Association for the Advancement of the Visual Arts`and the ‘Société Française de la Photographie’ (SFP). He belonged to a small group of Georgian innovators that took a lead in the development of photography in Georgia and the surrounding countries.

In the 1930’s, the Simon Janashia State Museum in Tbilisi, Georgia purchased the archive from the photographers relatives. The Ermakov Estate is the main part of the current museum’s photo archive. Since 2004 the Simon Janashia State Museum became part of the Georgian National Museum (GNM).

The Ermakov archive was rediscovered in 1999, as it happen with many things, after a coincident meeting during a holiday. This nearly complete archive comprises besides several camera’s and lenses, more than 20.000 original, primarily albumen prints; more than16.000 glass plate negatives (wet-collodion as well as gelatin), over 10.000 stereo photo cards and 127 photo albums. Only 116 of these albums are supposed to have been part of Ermakov’s working archive: three administrative indexes and 113 photo albums. The photo albums with around 20,850 prints played a central role in Ermakov’s photo archive as reference material. He published at least two sales catalogues in the Russian language, announcing systematic descriptions of more than 25.000 photographs. During his lifetime and after his death, Ermakov’s images were used for several reproductions and publications, mainly in the Caucasian and Russian region.

Figure 1: Interior of Ermakov’s studio in Tbilisi (albumen print, stereo photo card, courtesy GNM, Tbilisi)

Due to political interventions, changes in personal careers and institutional organization, the project outlines several times had to be modified.

First project setting

In 1999, as Georgia was a post communist country that was still in search for his identity, the existing museum structure (as well as other institutes) was definitely still Soviet style. This resulted in a very restricted accessibility of the archive and his content. In a way, this restricting structure during the past 70 years is a reason the photo archive material was little touched and still in a fair good condition. On the other hand, it was obstructing making a fair condition inventory, and demanding for a more personal approach. That year, Mr Hans de Herder, visited the archive and made a first inventory of the archive content. The board of the `Stichting Horizon` (Horizon Foundation) accepted his resulting project proposal and a project was born.

Figure 2: ‘Mzia’, the collection keeper of the photo archive and Mr. Hans de Herder in the archive room.

Part of this first proposal was the realization of a visitor room in the archive, in which future visitors had access to the archive content. Before renovation works started, the entire museum photo archive was moved to another floor and after completing of the renovation works, only the Ermakov material was moved back to the archive rooms.

Figure 3A & 3B: after renovation. 3A. Front visitors room and archive room entrance; 3B. Archive (back) room (situation 2003).

Realizing the renovation works and executing a preservation project must be seen in the context of this country at that time. This period the whole country suffers from regular failures of water, gas and electricity supply. Safeguarding of a regular electricity supply by means of a generator (on fuel), ensuring the continuity of working processes was absolutely necessary. Roads were not maintained and in severe damaged condition. Everywhere official and non-official guards or policeman were posted to check the drivers and passengers and to cash trespassing money. Distribution of food and materials from the countryside were problematic. So goods for preservation or conservation were not available at all. Equipment and furniture, storing racks, working tables, packing materials and enclosures (paper, board and boxes), computers, scanners, digital camera and reproduction stand … had to be imported and transported from abroad by ship and truck. The main business during the first period of the project runtime.

Preservation in Tbilisi and conservation in Rotterdam

It was not surprising, at that moment, there was no expertise in preservation and conservation practice of photographic materials available in Georgia.

The National Archives in Tbilisi, resorting under the Ministry of Justice, once were equipped with a well-known (in Soviet area) conservation studio for works of art on paper, manuscripts and books. Currently only a few people are still in service and the installations suffers from lack of interest and money. A second source for conservators is the National Academy of Arts, also located in Tbilisi. They are facing the same problems and the few conservators were mainly traditionally trained artists.

As the archive content had to be preserved but also made accessible, Mr de Herder first recruited (2003) two graduates from the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts, Ms Ellen Glonti and Mr Pridon Lobjanidze. They received a three-month practical training in digitization techniques and basic preservation treatments in the photo conservation studio’s in Rotterdam (NL). After a year it became clear the work proceeded rather slow and three other assistants were recruited (Mr Zurab Macharahvili, Mr Paata Grigolia and Ms Maia Makaridze). At the beginning of 2005, a group of three Georgian ‘assistant conservators’ were dry-cleaning album pages and stereo photo cards. The two ladys were responsible for the digitization of the original photographs with a flat bed scanner. Image descriptions were entered in the computer in a - modified to the Russian language - Adlib database. Project progress was followed up by regular working visits of the project coordinator, Mr. Hans de Herder, but also by the sending (by email) of weekly work status overviews from Tbilisi to Rotterdam.

Album conservation in Rotterdam

Many of the photographic albums were in a bad condition and were in need for conservation treatment. After discussing the needs and the required level of preservation and conservation, a pilot treatment was executed on albums A_031 and A_056 in 2002 in Rotterdam. Based on the results of this treatment and three standard representative images made from each photo album, individual proposals were made for the treatment of all other photo albums. The stereo card depicting Ermakov’s Studio in Tbilisi (Figure 1) with his photo albums lying on a table inspired in a way how the photo albums were to be conserved.

From 2004 on, selections of albums were transported between Tbilisi and Rotterdam. Before the photo albums went on transport to the Netherlands, the photo album pages and photographs were dry-cleaned and small repairs were made to the pages. Transports of photo albums from Tbilisi to Rotterdam were realized on a regular basis and special transport cases were bought for this reason. Each transport, depending on the size of the albums, contained between 4 and 12 albums. After finishing the conservation treatment, the albums were returned to the Simon Janashia State Museum. Between 2004 and 2006 the conservation of 49 photo albums was executed Rotterdam.

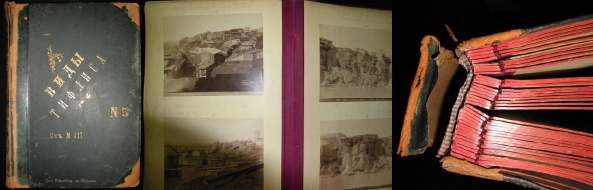

Figure 4. Album 18: front cover, album pages and top view of the back/binding (courtesy GNM/NFM)

Second period

2005 was an important year with many changes, when Mr. de Herder decided to interchange the field of conservation with a new passion. He left the job and country to set up a ‘Quinta’ in Portugal. Next to Mr. de Herder, Mrs. Mzia (the archive keeper) deceased, and also a new director was installed, a non-direct result of changes in the country governmental political situation.

The Rose revolution took place after disputed elections in November 2003 and the current president, ‘Uncle’ Edward Shevarnadze was forced to resign. After new elections in 2004, the opposition leader and nationalist Mickeil Saakashvili became president. Saakashvili’s pro western vision had influenced indirectly the project by installing a new museum director that was an international well known archaeologist, Mr David Lordkipanidze. Lordkipanidze started renovation works of several museums, to realize a more modern environment for the impressive national collections, the Ermakov estate content is one of these.

At the beginning of 2006, I (Herman Maes) came in charge as the new project leader. Also around this period, the Ermakov Estate received the status of National Cultural Heritage. A very good sign showing the government was aware of the cultural value of this material, but this status also resulted in a limited transport policy. Together with (untrue) rumors that the NFM had stolen some of the photo albums, a new strategy had to be developed.

Continuation of the conservation of the photo albums

In order to continue the conservation of the albums and being aware of the lack of practical expertise, a new training program was set up to bring the necessary expertise into Tbilisi. The person with the most practical skills and maturity, Mr. Pridon Lobjanidze, was invited for a three-month practical training in album conservation at the conservation studios of the NFM. Finally in the spring of 2008, Pridon left his country, without his wife and newborn daughter1, for a three month training to learn the basics of photo album conservation with the emphasis on hands-on training. During this training he learned about describing of all the parts of the photo albums in the right terminology, different bindings, the knowledge of materials used on albums, conservation materials and tools, problem solving, making of conservation proposals, and finally the documentation of the conservation process and the use of a documentation form.

It turned out that Pridon was talented and very successful in learning. After returning to Tbilisi, he started the treatment of a first group of albums. For this purpose, the GNM made available and renovated a separate room to function as a conservation studio for the photo albums. As the learning of conservation skills is an ongoing process, between 2008-2010 the process of learning was extended with four follow-up visits and hands-on training sessions of the NFM album conservator, Ms. Henriette Verdonk.

Follow-up training sessions in Tbilisi

The first follow-up training in October 2008 started with an update check of the damaged photo albums and their further treatment. The albums were divided in groups according to damage and materials. Evaluation of the work on the photo albums done in Tbilisi was an important part in the process of learning. Working together and sharing knowledge meant an improvement of skills and methods for pupil and teacher. Introduction of Tyvek© in album conservation gave a broader range of conservation possibilities: slim and strong bonds. And as specific bookbinding materials were scarce in Tbilisi, every visit started with the unloading of bags with bookbinding materials.

Figure 5. Henriette Verdonk and Pridon Lobjanidze in his studio in Tbilisi for the conservation of the albums.

Other ‘practical’ changes

The first renewed archive rooms were used as working area for the cleaning of the album pages and stereo photo cards. In terms of stability of the photographic collection, in 2006 all preservation activities were brought to the front archive (visitors) room and the photographic materials and equipment were moved to the back archive room. Only the heavy cabinets with the glass plate negatives were left in the visitors room until they were cleaned and repacked. Spare packing enclosures and boxes were also kept in the back archive room.

Figure 6A & 6B. 6A. Archive back room with cleaned and packed glass plate negatives; and 6B. individual packed prints in grey board boxes.

New approach for digitization activities

After completing the digitization of the nearly 8000 individual prints, further completion of the database should be realized by capturing images from the glass plate negatives. From this part of the collection were no indexes available. Before the glass plate negatives could be selected and scanned, they had to be unpacked, cleaned and repacked, time consuming. As the project started with the preservation and conservation of the photographic albums, we had a fair good idea of the content of the photo sale albums; these albums were nearly complete, comparing with the content of the sales catalogues.

To understand the relationship of the negatives, photo sale albums, photo indexes and sales catalogues, see the explanation in Annex 1. In the 19th century, it was common practice to add a descriptive text and inventory or negative number onto the negatives. By printing them in contact, the texts and numbers were printed together with the image. Most of the photographic prints in Ermakov’s working archive, as well the individual prints as the pasted prints in the albums, contained this strip with a descriptive text, negative number and a serial number.

All descriptive texts and negative numbers from the prints in the photo albums, together with a notation of the album number and album page number, were copied in a digital file, arranged and compared with the numbers and descriptive texts from the already digitized individual prints. In this way, by the use of the computer, we easily generated a selection of the prints from the albums that had to be digitized.

Individual prints were digitized by the use of a flatbed scanner, but was not suited for the use on the albums. As most of the digital images would be used in the database and not be used for duplication, the need for very large digital files was rather low. We decided to capture the images in the albums by the use of a digital camera.

Being complete or complete

We definitely had several discussions on what should be understood with complete. Doing as much as possible, or doing that what is available at a certain moment, or try to find all existing images as described in the sales catalogues?

Ermakov was a very active (business)man and sold a lot of single mounted photographs, but also tailored photo albums and portfolios on request. Outside the GNM, many Ermakov albums and portfolios are known, but these are not part of his catalogued sales system. The limits of what we describe now as complete, are the materials that were currently in the archive storage rooms and definitely were part of Ermakov’s working archive, not meaning they were made by Ermakov himself! So we excluded albums, prints and glass-plate negatives that were kept in other museums or archives in the country such as the Art Museum, the Karvasla Museum and the National Archive. But we also excluded some albums (for example an album with images from Japan), prints and negatives that were very unsure belonging to Ermakov’s working archive. Based on the available indexes, sales catalogues and sales photo albums, we could conclude that the Ermakov archive contained at the end of his life around 22000 images of mainly the Caucasian area, made by Ermakov and his ancestors. Many of the images on the stereo cards available in the sales catalogues that can be brought back to popular European, American and Asian images, are definitely copies.

By the completion of this project, an equivalence of nearly 90 % of the total records in the two Ermakov sales catalogues, together with their descriptions, were entered in an Adlib database system. All glass plate negatives were cleaned, packed in archival paper 4-flaps and stored in archival board boxes. Individual prints were individually packed in archival paper folders and stored in boxes. The conservation of the albums was not completed, due to delay and stuck of transport, but also due to the new approach.

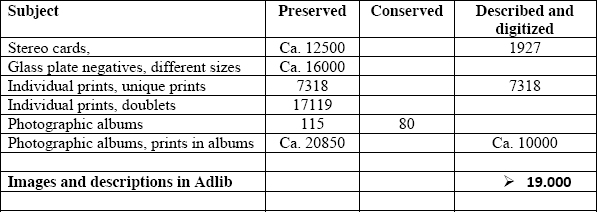

Next table shows a summary of the preserved and conserved materials from the Ermakov Estate, more details or brief descriptions of the specific materials can be found in the ‘Annexes 1 to 5’.

At the end of this project, or as we prefer to say, at the start of the continuation of the completion of the Ermakov-archive, all 5 Georgian colleagues received a working contract from the GNM. They will continue with the preservation and conservation of the albums and new adds into the archive. They have to take care and responsibility for an important part of their cultural heritage. And that is what I believe they will do.

At the moment of writing of this report, the (Adlib) records were not available for the public, but the decision was made to make the records available at the Georgian National Museum’s website.

This project has been made possible by the financial and logistic support of Stichting Horizon http://www.horizonfoundation.nl/projects/ermakov/ and the Flora Family Foundation. Some special thanks are going to our Georgian colleagues and their families for the ‘homecoming’ feeling every visit, this was very much appreciated.

MR HERMAN MAES

Is currently senior photograph conservator at the Netherlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam (NL) and was project manager of the Ermakov-project from 2006 until the end in 2010. He made follow-up visits twice a year to Tbilisi (Georgia).

MS HENRIETTE VERDONK

Is currently assistant photograph conservator at the Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam (NL). Ms. Verdonk is trained as a book and paper conservator and specialized in the treatment of photo albums. She was responsible for the training in photograph album conservation of Mr Lobjanidze and made four follow up training-visits to Tbilisi (Georgia).

Relationship between Ermakov Sales Catalogues, Indexes and Photograph Albums

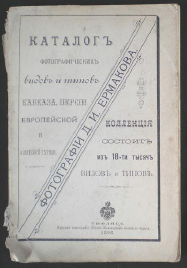

Ermakov Sales Catalogues

Currently we know about two so-called sales catalogues used by Ermakov, one edited in 1896, the second one in 1901. These printed catalogues were printed in the Russian language and contain around 25.000 entries or descriptions of single photographic prints and stereo-cards, all organized by region and type of origin of the depicted persons.

The second sales catalogue from 1901 announces 25.000 photographs for sale, of which 3.000 are stereo photo cards.

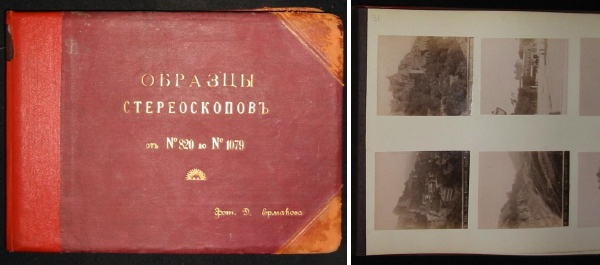

Figure 1.1. Sales catalogue 1896, 18.000 photographs for sale announced, from which 2000 stereo photo cards.

Ermakov Indexes

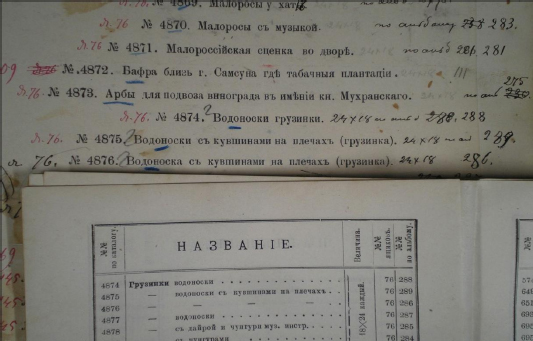

The Ermakov-archive contains various different indexes and catalogues. Only the above-mentioned sales catalogues and three large-format indexes – in similar bindings as the photographic albums – are believed to have once belonged to Ermakov. These Ermakov-indexes contain all the descriptive texts of the photographs in the same words as can be found on the strips underneath the negatives and prints. Some descriptions are just copies of these strips that were used to paste on the negatives.

Beside these printed descriptions, the negative sizes and negative box numbers were written by hand, most probably by Ermakov. These notes and descriptions correspond exactly with the printed descriptions found in the sales catalogues. More recently two similar indexes with descriptions of the stereo-cards were offered to the GNM, but the seller was not interested in selling the albums officially and the origin of the ownership is most probably disputable.

Figure 1.2. Descriptions in Ermakov indexes with examples of printed descriptions and hand written annotations compared to sales catalogue descriptions.

Ermakov Photograph Albums

The archive holds more than 127 photo albums. Only 115 of them are believed to have belonged to Ermakov’s working archive, and more specifically were some kind of sales albums. The albums contain Ermakov’s individual prints, all pasted on the album pages in a certain order. Ermakov kept the stereo photos in separate albums from the other prints, as can be seen in the sales catalogues. Some albums are missing, but the albums have more than twenty thousand prints pasted in them.

Figure 1.3. and 1.4. Album 110, cover and album page with stereo photo prints pasted inside.

Buyers of photographs (travelers) could first take a look at the images in the albums and make their own selections. The prints in the albums, as well the descriptions of the prints in the indexes and sales catalogues, were arranged by region, country, subject or type, thus making the selection of images very easy. Once a (group of) print(s) was selected, Ermakov could look into his stock with ready-made prints for their availability. In case prints were not available, he could look up the negative number and box number in the indexes and easily find the corresponding negative in the negative box to print from.

Sold prints were usually pasted on a board (sometimes with preprinted decoration and photographers credits) or in an album. As can be seen on many prints and albums made by Ermakov and kept in other collections worldwide, Ermakov signed his prints by using a blind stamp with his name. These blind stamps were not found on the prints in the photograph albums kept in the Ermakov archive, because these were ‘show’ albums and not made for sale. The individual prints in the Ermakov archive does not show these blind stamps either, because the blind stamp was added after the print was pasted on the board or in the album.

Perhaps this blind stamp can be seen as a mark for sold photographs to distinguish them from archive prints kept in collections of other archives.

Ermakov Stereo photo cards and their negatives

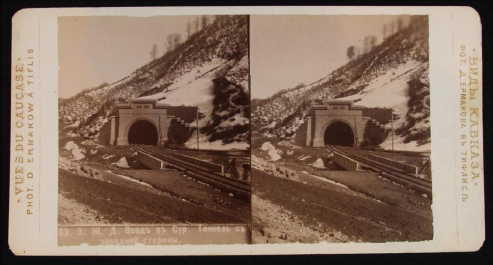

Stereo-photo cards became very popular during the 19th century. Ermakov offered stereo-photo cards for sale in his shop and we know that he copied many images from European, American and other origins. The copyright question seemed not a real issue that period, or had no effect on the photographer’s practice.

The archive also contains stereo photo cards and original glass plate negatives made by Ermakov and other photographers active in the area. The stereo photograph prints were contact printed from the glass plate negatives, from wet-collodion as well as from dry gelatin plates. To achieve a correct positioning of the two images, many of the glass plates for stereo printing are composed of two separate negative plates, kept together on supporting glass by paper strips.

Figure 2.1. Stereo glass plate negative, wet collodion emulsion. Two ‘half’ glass plates mounted by the use of a paper strip on a glass.

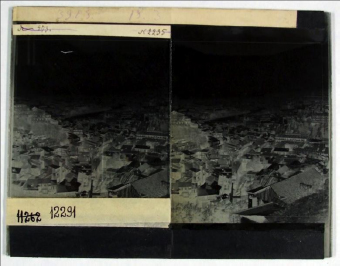

Figure 2.2. Stereo glass plate negative, gelatin emulsion.

Figure 2.3. Stereo albumen print mounted on a board with Ermakov’s photographer credits in French and Russian printed on the board.

Conservation of the cards and negatives

All available stereo photo cards were dry-cleaned by using small particles form grated erasers. After the dry-cleaning they were stored in PE-sleeves and placed in boxes, sorted by region of origin. Many of the stereo photo cards were available in more than one copy, and all of them were cleaned. A selection of the best quality prints was made for the digitalization process.

For the conservation of the glass plate negatives, see Annex 4.

Ermakov Photograph Albums, description and condition

A total of 127 albums was counted in the Ermakov archive. Only 115 of these are supposed to have been part of his working archive; three ‘albums’ in fact are the administrative indexes, thus 112 albums hold photographs.

Description of the photo albums

The photo albums were made between 1877 and 1906, individual and in series. They fit perfect the period comparing them with contemporary photo albums from Western Europe. The photo albums are case bound, paste-down albums with hard pages (cardboard laminated with paper or thin cardboard) and cloth hinges (Horton: type 3) and contain mostly albumen and collodion prints. There is one photo album with platinum prints. The photo album leaves are conventionally sewn or glued and hinged to bindings (Clarke) except one post and one concertina binding. The collection hold quarter leather (30), half leather (55), whole leather (4), whole cloth (20) and uncertain (4) bindings. The front covers are tooled and differ in detail: font, size and ornament. They were numbered on the back with red cloth embossed labels from the 1950s. There are 14 photo albums with printed grey or olive green frames with or without a golden rim and text. Little is known about the binders that made the photo albums. One bookbinders ticket of Otto Siebert in A_100 and a mark on the leather on the flesh side of the back cover of photo album A_018 of a sheep skin seller from London were found. One album was manufactured by Karla Scheiblera in Lodz, Poland.

Condition of the photo albums

Due to handling, storage, initial and later use of inferior bookbinders materials most of the photo albums were in a bad condition. From 1950 till 2000 the photo albums were stored vertical in four wooden cupboards with shutters in a hot (in summer) after naphthalene smelling room. For a long time the photo albums were looked upon as utensils. Sixty-seven photo albums have definitely been reinforced in a rather rough way at least once before. The cover material of twenty of these sixty-seven photo albums had been stripped totally and replaced by inferior material. Some front boards have been replaced, others were used as a back board, even on other photo albums. Reuse of original cover material as a spine lining is seen regularly. Pastedowns were removed, fly leaves were reused as pastedowns, so that the photo album could not operate properly. Endpapers were covered with new decoration paper. This all accompanied by loads of warm glue. Based on the marks and materials that were used, these repairs were done probably in the 1950s. The other forty-six photo albums stayed untreated when rediscovered in 1999.

Most of the photo albums showed planar distortion of the boards and the photo album block, dislocation of the back construction, torn album pages and surface abrasion of the albumen and collodion prints. This is not really surprising because the general quality of the materials used in the construction of 19th century albums was often poor. Another reason for damage on the photo albums is the way they were stored: people have a habit of placing books and albums vertically, seeing this as the most ‘natural’ way. However, the size of the albums and more specifically the weight of the photo album block – all album pages together – is damaging for the binding and hinged structure. The only way to prevent this is to store the photo albums horizontally.

Ermakov Glass Plate Negatives, cleaning and packing

The Ermakov archive holds only negative images in a collodion or gelatin emulsion on various thicknesses and sizes of glass. In this archive some identical images exist on different sizes of glass plate negatives. As the photographic printing papers used in this era were contact printing papers, different sizes of prints needed different sizes of glass plate negatives. This will be the main reason why we found different size negatives with exactly the same image.

In Ermakov’s archive several sizes of glass plate negatives were found, ranging from stereo glass plate negatives up to some 40 x 50 cm glass plate negatives.

Photoshop ‘avant la lettre’

We regularly found negatives in the archive with added black non-transparent paper and painted red areas. These areas influenced the final printing result, as covered areas diffused and sometimes even blocked the light that was exposing the paper so these areas remained lighter or even white on the print. Red paint was often used as retouching medium for the correction of damaged or undesired parts of the negative emulsion and image.

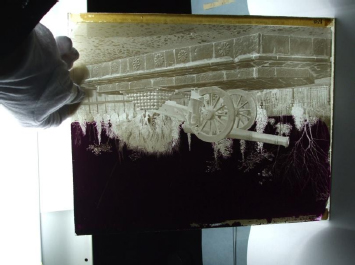

Figure 4.1. Painted areas on a collodion glass plate negative.

Preservation of glass plate negatives

In general the condition of the glass plates negatives is good to fairly good. Most forms of damage are related to the physical origin and support (glass), such as broken corners and fragmented plates. Some retouched areas show loss of retouching medium: the medium became brittle after ageing and often caused loss of emulsion (image). Gelatin glass plate emulsions showed some minor silver mirroring deposits around the edges; more exceptional larger areas of the emulsion showed silver mirroring.

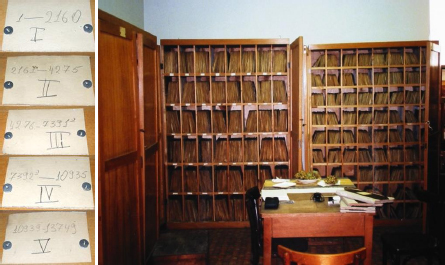

Nearly all of the glass negatives were stored, individually packed in paper envelopes, in 5 wooden storing cabinets that were divided in compartments that could each hold around 50 glass plate negatives. The size of the compartments was directly related to the size of the glass plate negatives and most probably the cabinets were specially made to hold the negatives.

Figure 4.2. The five labels pinned on the doors of the wooden storing cabinets and a look into two of the cabinets holding different sizes of glass plate negatives packed in paper or glassine envelopes.

After the Georgian Museum acquired the archive in the 1930s, new indexes with a new numbering system of the glass plate negatives were made. These indexes are still available in the archive but are not a leading instrument in cataloguing the images and negatives. These identification numbers are written on each individual paper envelop and also visible on the labels that are pinned on the wooden cabinets. (see also Figures 2.1. and 2.2. of the stereo glass plate negatives in Annex 2; the number written in black ink is the new identification number).

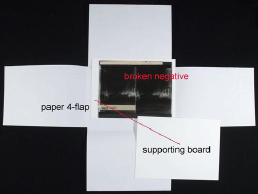

The main preservation actions were limited to the cleaning and repacking of the negatives in PAT certified paper enclosures, so-called 4-flaps, and fitting storing boxes. Before repacking, the negatives first had to be cleaned. The emulsion side was dry cleaned with a soft brush and the glass side was cleaned by using cotton swabs immersed in a water/ethanol (70/30) mixture. Retouched areas were not cleaned because the retouching media are part of the photographic object. During the repacking actions, descriptions of each glass plate negative were noted in a physical and digital file and the existing Ermakov identification numbers were written on the outside of each new paper 4-flap by using a pencil (HB). Each storing box received a unique number, related to the cabinet that the glass plates were stored in.

After the cleaning and repacking in a paper enclosure, the negatives were placed with their longest side down in the new storage box. In this way, the weight of the glass plates does not push on other glass plates. The new boxes were stored, sorted by box size, on the shelves in the storage room.

Figure 4.3. and 4.4. Cleaning and repacking of the glass plate negatives. Paata at work.

In case of broken glass plate negatives, a supporting board was placed under the glass plate and in the protective paper 4-flap. Broken glass plates were stored flat in separate boxes.

Figure 4.5. Standard paper enclosure (4-flap) for holding a (cleaned) glass plate. Illustration of adding an extra supporting board in case of a broken glass plate negative.

Ermakov Individual Prints. Repacking in new paper folders.

Print stock

The most important and maybe most valuable part of the Ermakov archive are the more than twenty thousand original – mostly gold toned albumen – prints.

Figure 5.1. Albumen print, negative number 17530, serial number 1477. Ermakov is the man with the white beard standing far right.

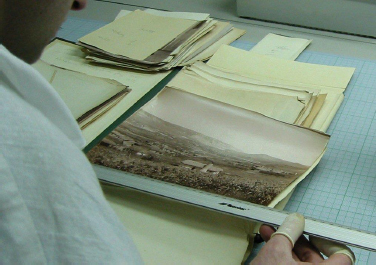

Most of these original prints contain a descriptive strip on the lower border with the negative number, image content description in Russian and an end digit, a serial number corresponding with a certain subject or series. The individual prints were originally kept in paper folders; each paper folder with the identification negative number(s) written on the outside. These paper folders were kept in groups in larger portfolio maps. This was Ermakov’s print stock from where he could take the prints ordered by his customers.

Figure 5.2. Albumen prints, paper folder and portfolio folders. Measuring the prints during their description.

Preservation of individual prints

Nearly all of the more than twenty thousand prints are still in excellent condition. The portfolio maps and paper folders they were kept in, were left untouched for many decades. The quality of the paper folders seemed fair, but the borders showed some discoloration and yellowing, indicating that the paper was breaking down.

Many of the prints were available in more than one copy, some were even available as more than 20 identical images. The quality of the prints was not consistent so a selection was made to keep the best print separate in an individual paper folder and paper file for the digitalization process. The doublet prints were bulk-stored in paper folders and special (grey, PAT certified) board boxes.

Figure 5.3. White portfolio maps with individual prints, the grey storage boxes can hold 5 of these maps.

Papers presented in Topics in Photographic Preservation, Volume Fourteen have not undergone a formal process of peer review.

1 Getting a travel-permit and a visa for the family was a time consuming and endless process. At the end, Pridon decided to leave the country without wife and kid.