The sculpture and court case featured in a Wall Street Journal article, was followed by blog posts by dalyconservation, the 1709 blog, Bloomberg.com, and the AIC blog. It also began a discussion on the Objects Specialty Group (OSG) distribution e-mail list. A representative of AIC wrote a follow-up letter to the Wall Street Journal, after consulting with other board members and AIC’s legal counsel, a statement has also been sent to the Wall Street Journal and The Art Newspaper about this article.

The discussion began by asking what response, if any, would be forthcoming from AIC about this article. The “restoration” removed original materials, replaced them with unsuitable materials, removed an original signature, and replaced it with the signature of the restorer and the restoration committee.

Mark Rabinowitz approached the issue playing the devil’s advocate and said “Conservation ethics leaves no question as to what is appropriate for the preservation of the artist’s original intent but it presupposes that this goal is consistent with the owner’s intentions. The owners, accepting that the changes they wished will interfere with the artist’s rights, specifically removed his association from the work, including erasing his name, and notified him to no longer consider this his art. This seems to be a case where the best intentions of the law have caused exactly the opposite result. Are we going to claim that owners have no rights to the objects they own and must only conserve them forever? If an owner knowingly destroys (or even improves!) a work of art with an understanding that by doing so he risks losing the association with the original artist, isn’t that a decision that their ownership entitles them to make?” He followed with another e-mail saying “Moral rights that are recognized after the sale entail destruction or modification that damages the reputation of the artist. Again, I believe the owners acted knowingly in order to protect themselves from such a charge by removing the artist’s name and notifying him that this is no longer considered a work of his.”

Linda Roundhill (with a nod to Vizzini the Sicilian) noted, “This was no innocent gaff due to ignorance. The artist offered to do the maintenance to preserve its [the sculpture’s] meaning, but the Federation completely shut him out of the process and deliberately (with intent) hi-jacked the artist’s work. ‘Inconceivable!'”

How could this have been prevented? Gary McGowan noted that “It does seem evident from this discussion that this was one of the issues directly germane to our organization developing certification. The industry, as a whole, would then be regulated through the certification process and there would be a less likelihood of either ambiguity or confusion over individuals’ abilities or credentials. I would state that it was not confirmed that the client was not interested in retaining the services of a conservator; rather they may not have seen the difference within the two disciplines. Since we are not a certified profession, many individuals do not see the difference between the two divergent fields. Far too often I hear the discussion of the ‘conservationist’. These abstract terms of ‘conservation, restoration or restorer’ can, and often do, confuse and blur the lines. With certification, I believe we would be better prepared to clarify the profession for our clients.” This was disagreed to by some of the members of the OSG-list, since the owner did not seem interested in conservation and would not have sought out a conservator, certified or otherwise. Victoria Book suggested that more visibility for conservators among artists also may have avoided this situation, if the artist had recommended a conservator this may not have occurred. Jerry Podany asked whether the owner of the sculpture actually knew about AIC and its services.

Many conservators wrote in to say they thought there should be an official response from AIC. There appear to be no responses from conservators (AIC affiliated or not) on comments section of the article the WSJ webpage. David Harvey suggested that the AIC should have released a clear and concise statement and he also listed comments suggesting what the statement should have said. Richard McCoy pointed out that as members of AIC “You and I are ‘AIC’ and if a stand is to be made, or if a statement is to be made than it seems to me it would be just as effective (and perhaps more so) if dedicated conservators were to be the ones making the stand individually rather than only relying on the Director to take a complex and nuanced position”. It was mentioned that while comments to articles are helpful “That’s no substitute for influence during art care planning and implementation. We would like that to be virtually automatic” Robert Krueger questioned whether a response would be needed “Responding and pointing out that this is not an approach a conservator would take is not a good way to advertise our field.” Steven Pickman gave two views about whether AIC should be involved in a response, “Should an intentional act by the owner responding to a set of conditions both artistic and legal be under the purview of AIC? I don’t think so.” He goes on to quote the purpose of AIC and how this purpose includes public awareness, opposition to any influences that lower standards, and the fostering of communication with other professionals involved in the guardianship and preservation of cultural property.

What can we take from this moment?

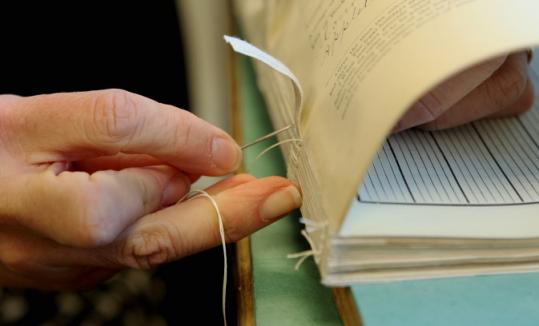

Jerry Podany summed up his thoughts about what this means in the bigger picture, he recommended that conservators pass along this article to their associates in the law profession that are interested in arts law. This could be a great “Teaching and outreach moment for other artists, collectors, administrators, and public regarding the proper care of sculpture, aspects of artists’ rights and the role of the conservator, as well as the limitations imposed upon the conservator by ethical guidelines.” Another point about materials emphasized that artists’ original materials should be maintained or replaced with similar materials, even though they may be unstable and require more maintenance. It is not enough to say that conservators have ethical guidelines but we must get across why we follow these guidelines and how complex this can become. David Harvey gave a number of suggestions about how conservators can have more outreach with the public.

At this point the conversation turned into a discussion of semantics and we discussed: conservators, restorers, conservationists, etc. and other names we have been called over the years. Richard McCoy suggested that we contribute to the Wikipedia page about conservation-restoration if we are interested in continuing this dialogue about our definition amongst the public. Nancie Ravenel suggested we educate ourselves about outreach through some upcoming online seminars about outreach and connecting to the public, available for free from IMLS and Heritage Preservation.

Tony Sigel responded to a side discussion about whether we are conservators, restorers, conservinators, etc. to say that some of what we do is restoration but we refer to it with other terms, making it difficult “To have the larger community understand what conservation is, what conservators do, and the relationship of conservation and restoration. Most of what we say about ourselves seems to try to disown such an important part of our work, to cloak it in obscuring jargon. I understand how the emerging field of conservation has, perhaps needfully, defined itself in opposition to restorers and restoration. But I’m afraid we may have disowned something important in the process that needs to be reclaimed – the practice, the idea, of restoration – that is an important part of our activities and identity.”

The discussion was interesting and challenged me to think and seek out more opportunities for outreach about conservation.

This is my first post for the AIC blog. The summary took a lot of time because every person quoted was contacted, given a draft of the post, and asked for their approval, via e-mail, of their quote. It is worth noting that I could have taken quotes from the OSG-list archives and posted them or forwarded all of the e-mails in this discussion as I wished, without the approval of anyone. I hope that this post continues the discussion about owner’s, artist’s, and conservator’s rights, and I hope that the distribution e-mail lists come to an agreement about how public or private these lists are and how information posted to these lists can be shared.